Although Vilnius is an increasingly popular destination for touristic purposes, the district of Uzupis is often ignored. Get to Uzupis as soon as possible. Why? Read on!

The most interesting parts of Uzupis are enclosed on three sides by the relatively narrow and shallow Vilnia River. Consequently, the district lies just to the south of St. Anne’s Church and the Church of St. Francis and St. Bernardino, and just to the east of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Holy Mother of God. Five or six road and foot bridges lead into the district, which is bisected from west to east by gently meandering Uzupio Gatve. All the bridges have padlocks attached to them, the ones leading to Uzupio, Paupio and Malunu gatves having the most. But what is the significance of the padlocks? They reveal that, on crossing the bridges, you enter the Independent Republic of Uzupis where freedom rules the roost, okay?

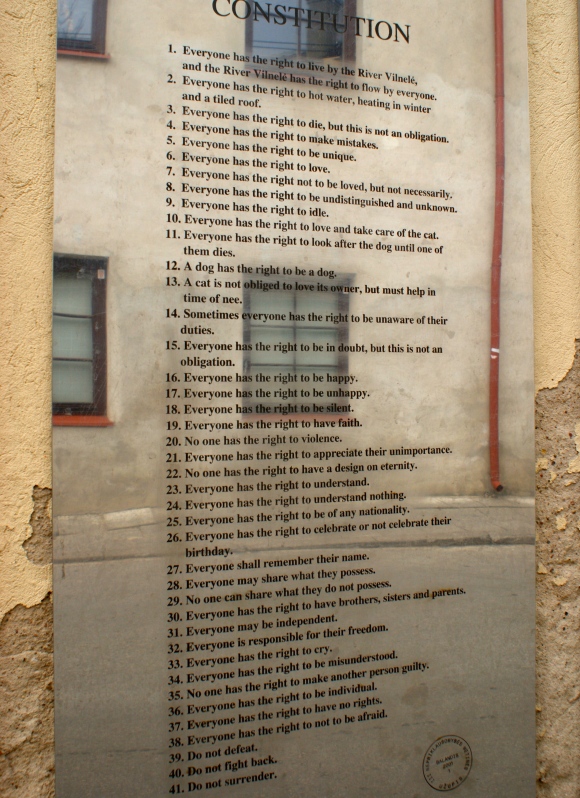

Uzupis is famous for being an unofficial breakaway republic of artists, squatters and drunks who have declared themselves a separate state from Lithuania. There is a constitution comprising of 41 statements found on metal plates attached to a wall near where Paupio and Uzupio gatves join. The statements have been written in different languages including Lithuanian, Russian, Polish and English. They combine the serious with the frivolous: everyone has the right to be happy, everyone has the right to be unhappy, and everyone has the right to love and to take care of the cat. In the middle of the small square where Uzupio, Paupio and Malunu gatves join, local people have erected the Angel of Uzupis on the top of a tall stone column.

The district of Uzupis extends east to Olandu Gatve, but the most interesting parts end where Uzupio Gatve divides into Polocko and Kriviu gatves. Because about a third of the most interesting part of Uzupis is now in ruins, small derelict plots await redevelopment (but the ruins and the derelict plots are remarkably picturesque, especially in rain or under grey and overcast skies). Another third of Uzupis is lived in by artists, squatters and drunks who occupy the somewhat rundown buildings that still have roofs on them, and the last third has benefitted from gentrification (Uzupis may have degenerated into a slum some years ago, but many old houses survived, albeit in a neglected state. It was only a matter of time before the area’s potential became apparent to young middle class Vilnians, not least because of its close proximity to the old and the new towns). Gentrification means that the area’s role as a haven for artists, hippies, squatters, new age travellers and drunks is slowly being undermined. Alternative lifestyles are being marginalised, not only by improvements made to the area’s housing stock, but also by the influx of more trendy shops, cafes, restaurants and art galleries. There is even a busy pizzeria serving food all day, and a branch of Iki, the popular supermarket chain (the local drunks appreciate the supermarket because it sells cans of beer for less than 2 litus each, which significantly undercuts costs in even the most rundown local bar).

Had I been one of the area’s alternative lifestyle pioneers, I would be upset to see how this once wacky and innovative community is being undermined by the influx of money and middle class beneficiaries of economic liberalism. However, what I saw is an area in transition with a bright future ahead. Uzupis has the potential to be one of Vilnius’s most attractive inner city suburbs because of the impressive mixture of buildings dating from the 16th century to the present day, the low hill on which it is situated and the absence of major roads that might bring excessive congestion and pollution. The river and the little pockets of greenery combine with a network of footpaths and narrow roads to create an area full of intimacy and variety rarely encountered in contemporary townscapes. I was drawn back on many occasions to examine the ruined buildings, the derelict plots, the gentrified courtyards, St. Bartholemew’s Church (the church is unusually small by Vilnius’s standards), the unsealed car parks behind houses and small apartment blocks, the terraces of single-storey wooden sheds and brick stores, and the gardens and grassy banks tumbling down the hillsides.